You always have the most of everything - of faith, of eloquence, of understanding, of keenness for any cause, and the biggest share of our affection - so we expect you to put the most into this work of mercy too.

2 Corinthians 8:7

It is very easy to forget where we have come from and how far we have gone to get where we are.

During one Christmas holiday - circa 1962/63, our family travelled to Tolaga Bay on New Zealand's East Coast. We briefly stayed with my great uncle and aunt. They had a small shop, not unlike those you see in and about the Pacific islands. You know the kind. A kind of smallish shed with a shutter that opened outward and upward. It was somewhat larger than a roadside stall because my great uncle and aunt lived there as well. What was surprising even to me as a little boy was that the floors were dirt, or as we would say today, 'rammed earth'.

We had a short stay. My great aunt cooked on a wood-fired cooker and we sat on wooden fruit boxes at a makeshift table. Even our beds were palliasses set up on the top of boxes. My recollection is that my great uncle and aunt were very generous hosts and our family albums recall our special visit. There may have been other visits, but I don't recall. I do remember the sadness of being told of when both my great uncle and great aunt died.

As an adult I look back in wonder at their frugal

lifestyle and imagine their poverty. And right now I think of how judgmental

those very thoughts are. I'm pretty sure that my great uncle and aunt didn't

give a tuppence about what life had dealt them. They were happy. They had a

home. They had a living. They had a community. They had each other, and they

had cousin Jane. They had the most of everything, and when they had nothing to

give, they gave of themselves.

By chance I found a mention of my great uncle in Joan Metge's book [Tauira: Maori methods of learning and teaching] during which an informant tells the author how Uncle Potene would attend gatherings at the school and teach the names of the streams, how they came to named and the legends that went with them. He had much to give and he gave it freely.

Paul was exhorting a somewhat well off Corinthian community to do more to support the poor (church) of Jerusalem. He wasn't asking them to give everything, just what they could afford. There are those who can afford to give money, some who can afford to give time. While today we all appear to be time poor, we are - many of us - reasonably well off. We can afford to make a difference in the lives of those who are in need - clothing, food, cash, shelter, work, furniture, expertise, advice or mentoring. But we ought not for one minute think that giving is a one-way street. Giving is a work of mercy. John Paul II in his second encyclical, Dives in misericordia (1980), constantly affirms that God's mercy is infinite and is made flesh in Jesus Christ. Jesus teaches, preaches and lives mercy, and for those who show mercy, they are truly blessed - indeed, Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy (Matthew 5:7).

My great uncle is a clear example of giving of himself when he himself possessed so little but the knowledge of his forebears. Be generous.

Peter Douglas

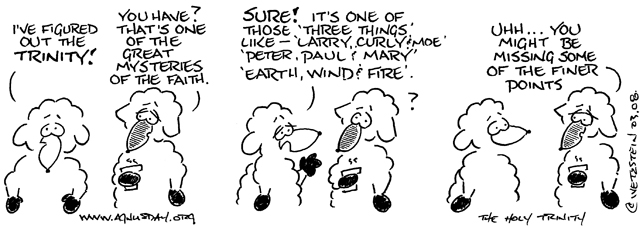

Great uncle Potene far left, at right my mother and great aunt. In front cousins Jane and Jock, brothers David, Richard and self.

They woke him and said to him, ‘Master, do you

not care? We are going down!’ And he woke up and rebuked the wind

and said to the sea, ‘Quiet now! Be calm!’ And the wind dropped, and all was

calm again. Then he said to them, ‘Why are you so frightened? How is it that

you have no faith?’ They were filled with awe and said to one another, ‘Who can

this be? Even the wind and the sea obey him.’

Mark 4:39 - 41

Our daughter returned home some months ago, part of the process of decision-making. We are again privileged to be a part of her daily life.

There is now more life in our home. But for our room and our daughter’s, the two other bedrooms are empty, their one time occupants now moved on, and perhaps never to return permanently. Those tidy bedrooms don’t make up for children who have to grow up and start looking after themselves.

Bit this is, after all, what we as parents aspire to. It’s our job. We have faith in our children, in the way we have taught them.

One of the richest, allegorical texts of Mark’s Gospel (4:35 – 41) is the story in which Jesus’ calms the storm. It has been understood as a picture of the confusion of the early church. Jesus’ questions his disciples, ‘Why are you so frightened? How is it that you have no faith?’ The disciples had failed to recognise Jesus’ presence, thinking him ‘asleep’. It is no surprise, that at the heart of this story, there is a story about who I am. It is no trouble being a person of faith when the going is good, but when my life is thrown into turmoil I struggle to see God walking with me. Notionally I know he is there, but in my anxiety doubt grows. Mark clearly tells us that his presence is constant and real, we need but call on his name.

And while this story still has an application to the life of the church today (clerical abuse, women and married priests, left-wing radical theologies, right-wing ‘traditionalists’, etc.) it is applies equally to letting our children go, to make their own decisions, to be independent, and trusting them to do right. They will experience life in a turbulent world, have enormous ups and downs, but in the end, we trust that they will know that you are there to love and support them. And, it’s our job. For the duration of our lives. And as we live in Christian hope for life eternal, it’s forever.

We have now returned to Ordinary

Time. Isn’t it time too that you returned to join this cycle?

Peter Douglas

CATHOLIC SCHOOLS AS COMMUNITIES OF THE WORD

Sacred Heart Catholic School, Ulverstone

by Beth Nolen in Liturgy News, Autumn 2021Many challenges followed the abrupt intrusion of COVID-19 into our

lives, including how to provide sacred rituals for students when there were no

(or few) students physically at school. Times of uncontrollable change shine a

spotlight on both strengths and cracks in our existing ways of working and

being, and reveal helpful insights. When we look back at the experience of

2020, there are key areas and core elements that, when conducted well, enabled

Catholic schools to flourish as authentic COMMUNITIES OF THE WORD.

1. Fostering relationships

Being deprived of our typical interaction with our communities

shed light on how much we need one another. At the end of our lockdown period

of ‘school from home’, curiosity drove me to ask my Y ear 8 son about his

thoughts on being home-schooled in the future. Mum, that’s a really bad idea. I

would have no friends, and I’ve realised that I actually need my teachers to

explain some things that I don’t understand in textbooks. We will never have

this conversation again! Unexpectedly, he has had no word of complaint about

school ever since, and a whole new way of working with purpose and appreciation

of his school community has developed.

Fostering genuine relationships is the basis for developing

authentic communities and is at the heart of Catholic schools being communities

of the word. One example comes from a Prep class at St Thomas More, Sunshine

Beach, Qld. In 2020, teacher

Tracy Flynn regularly invited parents to participate in the class

morning prayer ritual. When ‘school from home’ started, parents began asking

Tracy to share her class prayer. One parent independently created a video link

for the class to stay connected, and then Tracy received requests from parents

to lead her class for prayer. Participation via video allowed Tracy to see that

many children had created their own prayer spaces at home and some family

members joined in this time of prayer together.

My daughter’s school at St Dympna’s Aspley, Qld, sent home ongoing

resources using Microsoft Sway so that they could continue being a community of

the word while most students were at home. These resources engaged our family

in the story and the celebration, highlighting meaning through images, videos

of a small group of students at school completing various parts of the ritual,

readings from Scripture, reflections and prayers. I asked a staff member how

the school was able to create such high quality resources quickly in response

to rapidly changing conditions for celebrating liturgies. The answer was,

Relationships. We drew on people’s different strengths, including technology,

to bring it all together.

2. Nurturing spirituality

Email correspondence from a Prep student parent in Tracy’s class

at Sunshine Beach highlights what can happen through nurturing spirituality. A

parent describes how she was surprised

to find her daughter alone by a window early one Saturday morning,

so she asked her daughter if she was okay:

Yes. I’m just sitting

here with God, in here (pointing to her chest). How sweet!!! I said, That’s so

nice, Sweetie, that means you are never alone doesn’t it!? And she nodded. My

goodness what a beautiful moment. Thank you for your spiritual guidance!!

(Email between the parent and Tracy; used with permission from

both)

Although the term ‘spirituality’ does not have a universally

accepted definition (Adams..., 2016), Nye's ground-breaking work found that all

children have a sense of spirituality (Nye, 1998). Nye describes spirituality

for children and young people as recognising and supporting God’s ways of being

with them, and their ways of being with God (Nye, 2017). Her research has also

found that the younger the child, the more likely they are to seek spirituality

naturally by pondering the bigger questions of the meaning of life, death,

identity and purpose. There is also increasing recognition that spiritual

health is an essential component of adolescent health (Michaelsona..., 2016).

As children grow older, they may describe themselves as spiritual but not

religious, highlighting the broad definitions required for understanding

spirituality (Michaelsona..., 2016).

Nye (2017) reflects that, after spending time listening to

children talk about their spirituality for her research, they were frequently

unable to identify anyone else with whom they could continue these

conversations. To nurture spirituality, Nye recommends that adults respectfully

listen to our young people and allow them time and space to articulate their

deep questions about life and the meaning of their existence and their insights

into God; thus adults teach the use of silence. Adults create safe spaces that

allow students to ponder and communicate their experiences of awe, wonder, and

a wisdom and energy source beyond themselves that they may name as God.

Students build their capacity to engage in significant prayer rituals and

liturgies.

Understanding students' spirituality is invaluable for creating liturgical

rituals where students can find meaning and leave feeling challenged, nourished

and inspired to be the best version of themselves. Through my PhD research

focusing on what Early Years teachers need to build capacity to teach

Scripture, the rewards of focusing on spirituality as a

gateway for teaching religious education have become apparent.

Data from a Year 3 teacher revealed that, despite successfully enabling her

Year 3 class of 2019 to discover the riches of Scripture, she could not engage

her 2020 Year 3 class in religious education until she focussed on spirituality

first. It was then that exploring Scripture through religious education became

deeply meaningful. The major difference the Year 3 teacher identified between

the classes was that the 2019 cohort mainly came from families where religion

was part of family life. For most students in the 2020 cohort, this was not the

case. Therefore, nurturing spirituality became the access point in the

religious education of the class of 2020 for discovering rich meaning from

Scripture.

Spirituality refers to the student's interior meaning- making

journey, which is different from the religious education activity of

cognitively learning about faith communities and their religious beliefs and

practices, and different from participating in celebrating as a community of

the word. While all three are strongly interconnected, independently attending

to each element ensures time and intentionality for all three core elements.

When schools foster healthy relationships and engage well in all three

components, rich and deep meaning is attainable for all participants when

Catholic school communities celebrate the word of God.

A MODEL OF CORE ELEMENTS FOR CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS

Discovering

authentic meaning from religion.

How

is the mystery of God experienced?

What

opportunities exist for experiencing God?

How

is meaning found and expressed through participating in religious celebrations, religious rituals and

faith-based activities?

The model above builds on the model of religious education in the

religion curriculum for the Archdiocese of Brisbane (Religious Education

Curriculum P-12, 2020). Note the intentionality of all three elements, while

the goal of each element is to discover meaning. Faith is always invitational

through each element. It is also important to highlight that the element of

spirituality is not about teaching anything. Instead, it is about ensuring time

for reflecting, pondering and listening to how each person experiences wonder,

awe, mystery, transcendence and the deepest questions of life underpinning how

people choose to live.

3. Teaching prayer and Scripture

Recognising that students come to Catholic schools with diverse

backgrounds, there is a need for finding out what students know and understand

about prayer. Sr Hilda Scott from the Jamberoo Abbey in New South Wales

reflected on her experience at the Ignite Conference in 2016. In her view,

young people were thirsting for ‘understanding prayer’, and ‘to understand how

to connect with God’ (Scott, 2016). Therefore, teaching prayer is more than

merely teaching people to pray particular words. Sr Hilda’s own definition of

prayer is ‘God in communication with us’ (Scott, 2018).

Being a community of the word demands that we foster prayer skills

to experience ‘God in communication with us’. Teaching children how to use

silence is critical, especially in a world where silence can be rare. Mantra

prayer and breath prayer (focusing on every breath) are excellent for periods

of silence.

Similarly, exploring Scripture as literature, engaging in critical

thinking about the text, and pondering how the text reveals God’s dream for our

world leads to using Scripture well for prayer rituals and liturgies in

schools. Finding out about the text includes cultural insights, authorship, the

context of the text, and the genre of the text, which opens many new insights

for drawing a multiple layers of richness from the text.

4. Discovering meaning

At the end of the 2020 school year, I engaged in conversation with

someone who is not Catholic, who spoke about attending a Liturgy of the Word at

St Joseph’s primary school, Nundah, Qld, which she found deeply significant.

Students had ‘broken open’ the two different stories of the birth of Jesus, understanding

the Scripture stories so well they could explain their appreciation the

stories. In the liturgy, there was creativity, participation, deep

meaning-making – and no photography – as the community recognised this was not

a performance but a rich experience of the word of God.

The opportunity to teach students about Scripture before using the

texts for prayer rituals and liturgies affords Catholic schools a clear

advantage. Allowing students to bring their creative ideas to preparing a

Liturgy of the Word allows the potential for meaning- making through the ritual

to deepen significantly. The use of appropriate and diverse drama strategies

can draw attention to critical parts of the text. After the proclamation of

Scripture, students might enter the world of imagination to interview one of

the characters, the Bible author or even God. Recognising that Scripture has

the potential to speak to the heart of any person, countless strategies can

shine a spotlight on how the text calls people to live today. Encouraging

students to identify multiple interpretations of Scripture ensures a deeper

understanding of the power of the text. Anything that encourages participants

to discover deeper levels of appropriate meaning from the word and the ritual

will help create powerful experiences where people are engaged, challenged and

inspired to be their best selves when they leave.

Ponder what aspects of the liturgy we want to highlight to

strengthen participants' meaning- making. Identify when students may be in

danger of ‘going through the motions’ rather than understanding the

significance of what they are doing. Respond by leading ‘mindfulness moments’

such as pausing during each action to make the sign of the cross. In the name

of the Father – we pause to think about God’s love in our lives; and of the Son

– we pause to remember the presence of Jesus here with us; and of the Holy

Spirit – we pause to recall how God’s Spirit is actively at work in our hearts.

Seeking feedback allows leaders to fine-tune how to provide

valuable prayer and ritual experiences. Strategies such as making time for

journal writing, respectful listening or anonymous feedback posts in a safe

environment can enable students to respond to questions such as, What meaning

did you find through this experience? How did this experience challenge you?

How did this experience inspire you to be the best version of yourself?

Even casual conversations with students can reveal deep insights,

as I found while talking with a Year 8 student at a social gathering in 2020,

when he stated, I think we should have more liturgies at our school. When

pressed to answer why, the student paused to reflect and then replied, Because

they remind us who we are and who God wants us to be. That student showed a

surprisingly deep understanding of why we continue celebrating as communities

of the word, even during the challenges of living in a pandemic.

Catholic schools can provide profound experiences of being a

community of the word, where participants listen with their ears, minds and

hearts, and leave wanting to return because the experience has enriched their

lives. Catholic schools have the gift of being able to provide three core

elements that invite people to discover meaning: through religious education

that engages students and leads to critical thinking; nurturing and listening

to the spirituality of students; and participating in religious celebrations,

rituals and faith-based activities. When all three elements are conducted well,

within an environment that intentionally fosters healthy relationships between

students, parents and staff, Catholic schools flourish as COMMUNITIES OF THE WORD.

Beth Nolen is doing

doctoral studies on building the capacity of Early Years teachers for teaching Scripture. She works as an Education Officer -

Religious Education for Brisbane Catholic Education.

Adams, K., Bull, R., &

Maynes, M.-L. (2016). Early childhood spirituality in education: Towards an

understanding of the distinctive features of young children's spirituality.

European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(5), 760-774.

doi:10.1080/1350293X.2014.996425

Michaelsona, V., Brooks, F.,

Jirásek, I., Inchleye, J., Whiteheade, R., Kingb, N., . . . Pickett, W.

(December 2016). Developmental patterns of adolescent spiritual health in six

countries. SSM-Population Health, 2, 294-303. Retrieved from

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S2352827316300052

Nye, R. (1998). Psychological

perspectives on children's spirituality. University of Nottingham, Retrieved from

http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11177/1/243253.pdf

Nye, R. (2017). Spirituality

as a natural part of childhood. Retrieved from

https://www.biblesociety.org.uk/content/explore_the_bible/

bible_in_transmission/files/2017_spring_v2/transmission_spring_20 17_nye.pdf

Religious Education

Curriculum P-12 (2020), M. Elliot, L. Stower, & A. Victor eds. Brisbane:

Catholic Education Archdiocese of Brisbane

Scott, Hilda. (2018). Words

from the heart: episode seven. Wisdom from the Abbey: Prayer. Retrieved from

https://www. shalomworldtv.org/wisdomfromtheabbey

God’s ‘conduit’ Sr Hilda

Scott: ‘I can’t do anything without Him’. (October 2016). Retrieved from

https://catholicleader.com.au/ people/gods-conduit-sr-hilda-scott-i-cant-do-anything-without-him