Behold the bread of angels, sent

For pilgrims in their banishment,

The bread for God’s true children meant,

That may not unto dogs be given:

Oft in the olden types foreshowed;

In Isaac on the altar

bowed,

And in the ancient paschal food,

And in the manna sent from heaven.

Come then, good shepherd, bread divine,

Still show to us thy mercy sign;

Oh, feed us still, still keep us thine;

So may we see thy glories shine

In fields of immortality;

O thou, the wisest, mightiest, best,

Our present food, our future rest,

Come, make us each thy chosen guest,

Co-heirs of thine, and comrades blest

With saints whose dwelling is with thee.

From the Sequence for the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of

Christ

An article in the Jesuit's America magazine this week revealed the growing attraction of young people to Eucharistic adoration (click here). Its author, Peter Feuerherd, suggests that the appeal of Eucharistic adoration for college students is - given the stresses of study during the pandemic - that Eucharistic adoration offers a place of silence and reflection and freedom from technology.

Parishes throughout Tasmania continue to provide this

opportunity on a weekly basis. Also reported this week in St Joseph's Church in

New York's Greenwich Village is building a chapel dedicated to the perpetual

adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. Dominican Father Boniface Endorf, pastor of

St Joseph's, believes that the adoration chapel will be, "a source of

grace for vocations among those who visit; to help ordinary Catholics to grow

in holiness; to aid in the strengthening of marriages in the neighbourhood; and

to provide spiritual healing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Beginning with the reservation of the Eucharist for those who could not attend Sunday worship Eucharistic adoration grew out of an understanding of the Real Presence - beginning with Gregory VII and later popularised by St Francis of Assisi. The feast of Corpus Christi was established by Urban IV assisted the growth of the practice of adoration but by the 19th century the phenomena was universal throughout the church with entire religious congregations established for the perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

Paul VI far from downplaying adoration promulgated (during the Council itself) Mysterium Fidei in which he called for its tireless promotion - not its suppression. Both Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI explicitly called for the practice to be encouraged.

What has never changed is that adoration (including exposition and benediction) is an invitation. An invitation into deeper relationship with Christ. It is one way, but not the only way. In 1973 the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship clarified that Eucharistic exposition and benediction were no longer considered to be devotions, but rather are a part of the Church's official liturgy. In the past benediction was frequently added on to the end of another service or devotion, though this is now no longer. Eucharistic exposition and benediction is a complete liturgical service in its own right.

In as much as the church provides for a variety of liturgies and devotions, the highest obligation is that you participate in the weekly celebration of the Eucharist - and - leave Mass committed to take the Gospel to the world.

Peter Douglas

When my children were quite young, I would sit and just look at them during their sleep in wonder and amazement about the bounty in our lives, and what miracles these gifts were to us. They were and are unique.

When Moses first encountered Yahweh he knew little about this God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Indeed Moses insisted on ‘knowing’ who this God was. ‘I am who I am,” answered God. Moses was in awe. From this time to the Maccabees, this God continued to reveal himself, evolving over time (from our human perspective) into a God of mercy, compassion, rich in kindness and faithfulness. This God was also called Spirit (Ruah), for he breathed life into his creation and the wind itself brought good fortune and good news.

For we Christians, a deeper revelation becomes evident in Jesus’ relationship to his God whom he calls Abba, Father. The early apostles, certainly the writers of Matthew’s Gospel and Paul were using a liturgical Trinitarian formula (most specifically Matthew’s injunction that the disciples must baptise ‘in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit’). The doctrine was then defined by early general councils of the Christian church. The Council of Nicaea in 325 and the Council of Constantinople in 381 declared that the Son is of the same essence as the Father, and that the three Persons are one God. Differences still remain in the eastern and western churches. In the west, theologians such as Anselm and Thomas Aquinas continued to refine this teaching. Since this medieval work there have been few further developments, though today’s thinkers are attempting to link this teaching with the daily lives of the faithful.

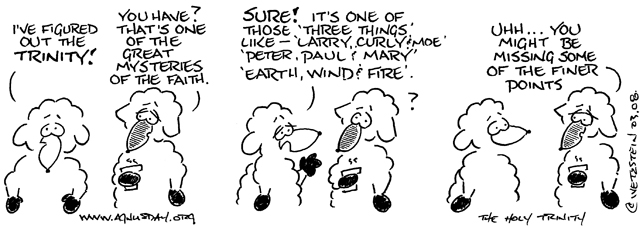

For many the Trinity is a most difficult idea to grasp, and it is often

dismissed as a mystery to which only the likes of theologians can access.

Perhaps we need a new set of paradigms, or new metaphors to help us digest and

understand. Can I suggest, however, that a ‘Moses’ experience, meeting God face

to face – in relationship, will always be at the core of this understanding?

When we meet God in our prayer, in our liturgy, and through our community and

communion, we place ourselves before him saying, ‘Lord, here I am, I come to do

your will.’ His response is, ‘I am your God, I am who I am (Yahweh), come to

me.’ We are his children and his

creatures, it is his life that is breathed into us, and I have no doubt that he

looks at us in the same way I looked at my young children, with wonder and

amazement. We too are mysteries - unique and miraculous.

Peter Douglas

This short reflection has

appeared in this blog previously.

No comments:

Post a Comment